A much-beloved classic that is essential to any major car collection is coming into its own.

Original Article – BloombergBusiness – December 17, 2015

The original Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing is the most collectible Mercedes on the market today. Depending on how you define “collectible,” that is.

“It’s the most collectible postwar Mercedes hands down,” said Phil Skinner, the collector car market editor for Kelley Blue Book. “The car is an icon. Beautifully crafted. Beautifully styled. An absolute performance vehicle. If you want to get the ultimate Mercedes, the 300 SL is the pinnacle.”

Robert Moran, director of Mercedes communications, is a little more circumspect.

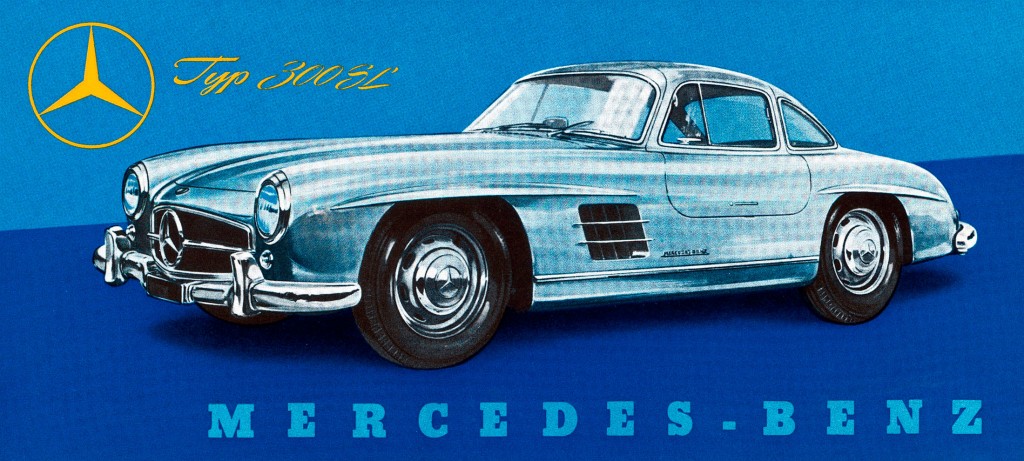

The 1954 Mercedes 300 SL debuted the first use of direct petrol injection in a production car. Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

“The rarer Mercedes race cars are more valuable than the 300 SL—they’re in a completely different stratosphere,” Moran said, noting one W196 that sold several years back for nearly $30 million. “When they come up on the auction block, they are dominant.”

McKeel Hagerty, chief executive officer of Hagerty, sees it all with a little more nuance.

“Look, we’re talking about the best here,” he said. “If you like good wine, you can buy very good California cabernet. Some aficionados may say they’re good, but they’re American-style and a bit gauche, so true Mercedes connoisseurs say the race cars are rarer and better, like a French Bordeaux. But the gullwings are like a really great California cab: They’re really expensive, and you can’t deny how good they are.”

Indeed. The 300 SL is a true collector’s vehicle regardless of whether it lands in the premier spot of a given group. It is a foundational pillar of a complete collection. And right now, it’s hot.

Supercar Patriarch

The Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing. The in-line six-cylinder engine had top speeds up to 161 mph. Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

The 300 SL was the first production gullwing car created and is the grandfather of the modern SLS AMG, the $222,000, 583-horsepower gullwing coupe. “SL” stands for the German phrase “Sport Leicht” (sport light), so-named for its lightweight aluminum chassis and sporty tubular body (more on that later); the 300 refers to its 3.0-liter inline six-cylinder engine.

Mercedes debuted the 300 SL at the New York Auto Show in 1954, where it became an instant success largely because of its iconic doors but also because of its link to success on the track; its direct predecessor, the W194, had won prestigious races like the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Eifelrennen at Nürburgring, and Mexico’s Carrera Panamericana.

The story goes that Mercedes’s New York distributor, Max Hoffman, followed the wins closely and suggested to the boys back at corporate that affluent Americans newly wealthy post-World War II would certainly buy a road-legal version. So Mercedes decided to give them one.

Design Delight

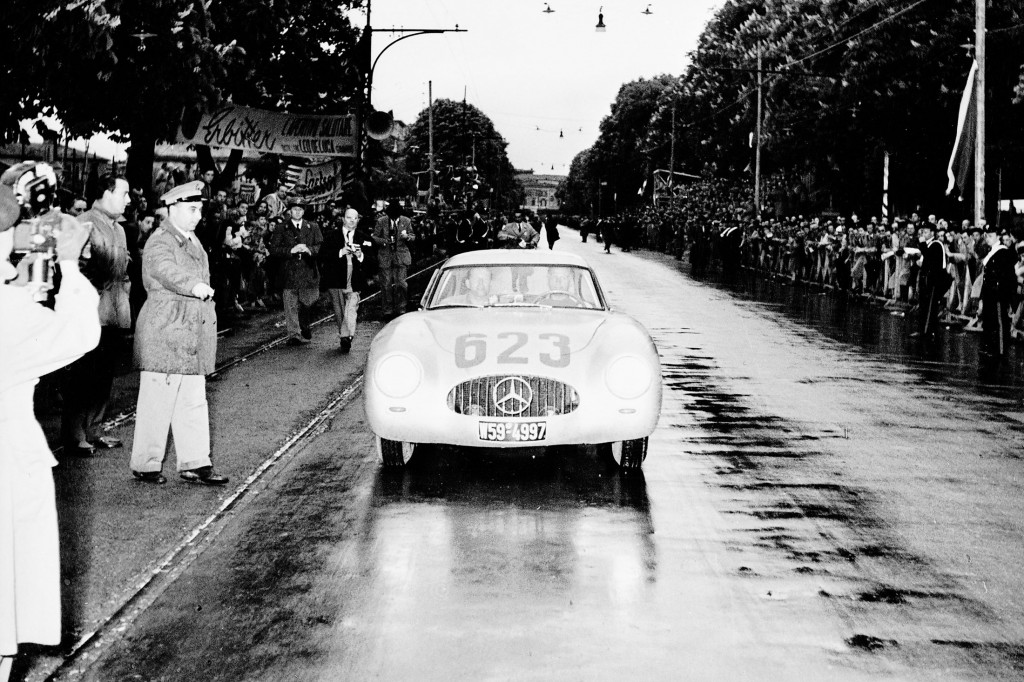

The Mille Miglia, 1952, second place: Karl Kling/Hans Klenk with the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL racing sports car (aka the W194 model). Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

The 300 SL had a welded aluminum tube chassis designed to compensate for its relatively underpowered engine; its main body was steel, with a hood, doors, and trunk lid all made from aluminum, to save even more weight. So the car was light (just over 3,400 pounds) and strong, but its design also made traditional doors impossible. Which is exactly why Mercedes developed the doors-open-up style.

“Those doors were almost an afterthought,” Moran said. “It’s one of these form and function details that have become part of its allure.”

Aerodynamics helped determine that famous form as well: Engineers placed those straight metal “eyebrows” over each of the wheel openings to reduce drag.

And that odd body shape also birthed the “power domes” on Mercedes hoods that we’ve seen so many times since its era. The domes—slight bulges in the hood—were made to accommodate the inline-six engine in the 300 SL, which had to be tilted up at an unusual angle in order to fit in the unnaturally low front cavity. One of the small bumps in the hood was made to fit over the top part; the other was added just to match the first.

“The first was functional, and the second was functional aesthetically,” Moran said. “It was all about symmetry.”

Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Coupe in the Mille Miglia. Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

Under the Hood

Under those domes, the SL had the world’s first-ever production direct-injection engine, which had barely been featured yet, even in race cars. It was the supercar of its day, with more than 200 horsepower and, at one point, the world’s fastest top speed for a production vehicle: just over 150 mph when it debuted, and 161 mph a year later. It could hit 60 mph in eight seconds.

Paired under the engine was a rear suspension design with a dual-pivot swing axle famously prone to slipping and sliding and oversteering at every opportunity (the roadster featured a redesigned single-pivot axle, which made the car much more neutral to handle and less prone to oversteer). It had progressively precise steering, a four-wheel independent suspension that made it comfortable to drive, a four-speed manual transmission, and even air conditioning on later models.

The 1954-57 Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing. Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

Think of it as the historic equivalent to the modern McLaren F1 or Ferrari LaFerrari. Driving one, Moran said, is a life-changing experience.

“It is basically a race car: It’s got an amazing engine that wants to run all day, the handling is great, it makes all these amazing noises,” he said about the all-black 1955 300 SL he drove for days during the famous Italian Mille Miglia car race last year. “It does run a little hot, so when you pull in to get gas, you open the doors to let it air out a little, but you’re also putting on the greatest spectator show. People go nuts. It’s instant international relations.”

Moving Mercedes Forward

In fact, the 300 SL changed Mercedes’s image in America from that of a quiet German car company that made staid luxury sedans to one that could also dominate a field of high-performance whips. Sophia Loren, Tony Curtis, Clark Gable, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Stavros Niarchos all owned one.

The Mercedes-Benz 300 SL came with a spare tire, a set of luggage, and, in later models, air conditioning. Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

Of course, all that cachet comes with a price. Original 300 SLs had a starting price of around $11,000, more than twice as expensive as the general $5,000 Cadillac convertible. Mercedes made only 1,400 or so before switching to the open-top roadster version, heavier but easier to drive (better brakes, better suspension, that single rear axle), in 1957.

And since then, well, the sticker price has skyrocketed. In 2014, Russo & Steele sold a ’56 Gullwing SL for $1.32 million; earlier this month, Bonhams sold a ’55 Gullwing SL for $1.34 million. Next month in Arizona, Gooding & Co. will offer three of them, the cheapest of which is listed with a low-end estimate of $900,000.

“The values are astronomical now,” Skinner said. “The cost of a 300 SL is going to be between $1.8 million and $2 million on average for the coupe.”

Interestingly enough, the 300 SL is one of the few models where the closed-top car is worth more than the open. While gullwings may do up to $2 million, roadsters generally hit between $1.4 million and $1.6 million. That’s because of the coupe’s singular gullwing design, which didn’t reappear again on the production market until the 1970s and ’80s (C111 or DeLorean, anyone?), and because the coupe was closer in design and philosophy to the original racers.

Like the 300 SL Gullwing, the Roadster was the vehicle of choice for those with a taste in both aesthetics and high-level engineering. With a list price of $11,000 in 1954, ownership of a new 300 SL was a dream for most. Source: Tim Scott/RM Sotheby’s via Bloomberg

Either version, though, makes men drool.

“The cool thing about both the Gullwing and the Roadster 300 SL is that if you have the money to buy one, any single one of them, you know you have a world-class car,” Hagerty said. “There are rarer Mercedes, but no one is ever going to look at an SL in someone’s garage and thumb their nose at it.”

The SL is one of the few cars that have universal appeal, with consistent strong interest from the top collectors the world over. Unlike, say, a Chevrolet Corvette, which is popular to collect for American buyers but not as much for European or Asian money, the Mercedes-Benz SL is not regionally specific. According to data from Hagerty, the average price of a 1956 300 SL Gullwing in 2006 was $450,000. This year, it’s $1.6 million. Similarly, a 1962 SL Roadster averaged $350,000 in 2006; now it’s $1.7 million.

Here’s your caveat, though: The SLs have become more prevalent on the auction block in recent years. Last summer at the Monterey auctions, the number for sale was close to 30; it was more like a dozen or so in previous years. The explanation is simple: People who realize they have a million-dollar opportunity sitting in their garage tend to want to sell. Hagerty said the increased popularity will eventually slow the stellar investment gains but that the car’s increasing value will remain “very stable” for the foreseeable future.

Mercedes head of communications Robert Moran raced a ’55 300 SL in the famous Mille Miglia race. Photogapher: Robert Moran/Courtesy of Mercedes-Benz USA

“They absolutely have proven to be good investments,” he said. “For a buyer looking for that world-class car but who doesn’t want to spend $6 million on something more rare, they’re very safe cars to buy.”

(Pssst, here’s a car-world life hack: If you want something similar to the 300 SL but don’t have the extra million, consider the smaller 190 SL coupe, which looks similar but usually sells for closer to $120,000.)

Classic Give and Take

Those who do go for the big fish will reap plenty of joy, experts say. The SL is one of the few blue-chip vintage cars viable as a weekend driver—even if its affections don’t come cheap. Like any high-performing athlete, it requires close maintenance.

The Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing (model series W198 made from 1954 to 1957). Source: Mercedes-Benz USA

“You do have to worry about the care and feeding of the SL,” Skinner said. “It’s not like a modern car where you can just hop in and turn the key and go for a ride. You’re looking at a $12,000 or $13,000 repair job just to get something like the radiator replaced.”

Not that anyone who paid $2 million for a weekend driver is going to quibble over 10 grand. On the contrary, in this rarified air, to pay such a pittance is considered part of the privilege.