Original Article – Car & Driver – 2015

With 2015 marking its 65th year, the Pebble Beach Concours d’Élégance, held on the 18th green at Pebble Beach Golf Links, is the world’s premier vintage-car event. The coveted Best of Show trophy at the Concours is the holy grail of the old-car world. As a Pebble Beach judge for 26 years, I’ve witnessed the joy of victory and the agony of defeat countless times. Jay Leno, a frequent entrant, likes to say that “this is the only car show where a simple millionaire can beat the billionaires.” But it’s much more serious than that. Here’s a look at what it’s like to judge the world’s most prestigious car show.

Let’s start with the cars. To show a car at “Pebble,” you first must be invited to apply. Each year there are about 220 places on the lawn, and while invited applicants are roughly that number, many hundreds more contact the concours each year on their own to apply. It’s hard to get in, difficult to win your class, and nearly impossible to capture the top prize. The finest and often the rarest automobiles ever built are divided into as many as 30 classes, several of which may change each year.

Splendor in the Grass

Entrants often work for years to restore their cars, although well-preserved cars are equally welcome in the Preservation Class. From the moment the show cars emerge out of the early morning mist and take their assigned positions on the 18th green in front of The Lodge, Pebble Beach becomes a colorful and dramatic pageant. Suspense builds throughout the day. While elegantly dressed men and women sip champagne and crowd around the cars, knowledgeable class judges in blue blazers meticulously scrutinize each car for restoration accuracy or preservation integrity, as well as for mechanical function. Points are deducted for any imperfections, inaccurate details, and over-restoration, and are awarded for style, beauty, color, and field presence. A perfect score is 103 points. Each winning entry must be driven over the show ramp to claim an award.

A class victory at Pebble Beach confirms that a car is historically correct, very close to the way it originally came from the factory or coachbuilder, and arguably perfect. But even that’s not enough. From those class winners, the Best of Show is chosen by a secret ballot cast by the Chief Class Judges, along with a cadre of Honorary Judges, many of who have been or are presently automobile designers, along with the event Chair, Sandra Button.

A 1937 Delahaye at the 2015 Concours.

Any Pebble Beach award increases a car’s value, compliments its owner, and honors its restorer. Once you and your car have won an award at Pebble Beach, recognition follows you throughout the old-car world. Multiply those accolades by a big factor for winning Best of Show. Although a few past Best of Show winners have restored their own cars, most have been restored professionally. Very few people have the talent or the equipment to do a car on their own.

“Winning Pebble Beach establishes your shop as a brand,” says Paul Russell (whose entries for Ralph Lauren and for Paul and Chris Andrews have won Best of Show three times), “and it establishes the credibility of the winning car. There’s not much you have to say after that. You’ve added another important chapter to the car’s story.”

Serving as a judge at Pebble Beach is a great honor. I have done it 26 times, and it’s still a thrill. This is what it’s like.

The Long Road to Pebble Beach

It all starts with car selection. The Pebble Beach Selection Committee—of which I am a member—meets in March. During the three-day meeting, which usually involves a side trip to a prominent collection or two, we review the applicants and finalize classes. Applicants send lots of information on their cars including vintage and recent photographs, the car’s history, provenance documents such as old registrations, previous awards, etc. You can’t carbon-date a car, but it is easy to fake photos and documentation, so we like to see as much information as possible. The combined automotive knowledge on the committee usually ensures an applicant’s car is the real deal—we don’t accept replicas—but we can’t be too careful. Each of the 14 members is an expert on several makes. Their combined knowledge helps ensure we don’t accept any ringers or fakes.

We vote to accept or reject each car. Sandra Button, as chairperson, has final approval. The results are posted on a special website that only the committee members can access.

The official Pebble Beach Concours acceptance letters—addressed to the owners of all the cars that have been approved—are then mailed, usually in April, to their delighted recipients. Rejection letters are sent at the same time. Class Judges receive assignments shortly afterward.

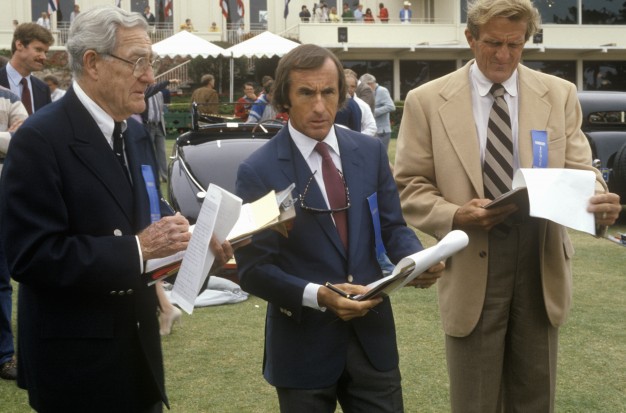

Racing legend Jackie Stewart, center, has been a judge at Pebble Beach. Flanking him here are the late Otis Chandler, left, and Briggs Cunningham.

Here Come the Judges

The strength of Pebble Beach lies in its judges and its judging system. Pebble Beach judges are the most qualified experts available. Many have been Pebble judges for decades, and they often judge the same classes each year. They know the cars; they know the details, from correct hose clamps to paint type. “We’re preserving history,” former Chief Judge Ed Gilbertson likes to say. Generations from now, people will look back on these cars and know, that for this moment in time, they were the best they could be.

Depending upon classes, we will have about 100-to-110 class judges and about 50 Honorary Judges (more about them in a moment). Most class judges have gained prior experience as CCCA (Classic Car Club of America) or AACA (Antique Automobile Club of America) judges. Ferrari, Rolls-Royce, Bugatti, Bentley, and other important marques are almost always judged by qualified people from those marque clubs.

The Chief Judge is Chris Bock, from Nevada City, California. He attended the event for the first time at age 18, and has been a Judge or a Chief Class Judge since 1973. Glenn Mounger, formerly co-chairman of the event for many years, is the Chief Honorary Judge. Jules Heumann, Pebble co-chairman from 1972 to 1998, is the chairman emeritus. He’s over 90 years old and sharp as a tack. As you can see, long experience abounds. We have twelve judges with more than 30 years experience at Pebble, thirteen judges with 25 years experience, and eleven judges with more than 20 years experience. Chris Bock told the assembled judges this year that the combined Pebble Beach judging experience in the room exceeded 1970 years.

Honorary Judges are industry luminaries and many of them are automotive designers, retired and active. This year, Honorary Judges included former Chrysler design chief Tom Gale and the present head of Fiat-Chrysler Design, Ralph Gilles; Pulitzer Prize-winning author Paul Ingrassia; former racer Jochen Mass; former Mazda head of design Tom Matano; Gordon Murray, the designer of the McLaren F1 and the Mercedes-Benz SLR; the Wall Street Journal auto critic and Pulitzer Prize winner, Dan Neil; Jackie Frady, Director of the National Automotive Museum; Sir Jackie Stewart, former F1 champion; racing icon Sir Stirling Moss; and Design Directors Christopher Svensson (Ford Motor Company), Freeman Thomas (Ford Motor Company Strategic Design Group), Dave Marek (Acura Global Design), and Shiro Nakamura (Chief Creative Officer for Nissan Motor Corporation), to name just a few. Past Honorary Judges have included Bob Lutz, Jim Farley, Keith Crain, Parnelli Jones, Piero Lardi Ferrari, and the late Denise McCluggage.

Dawn Patrol: A ’51 Mercury custom enters the show field.

Chief Class Judges and team members include this writer, along with Leigh and Leslie Keno (whom you may know from Antiques Roadshow); restorers Scott Grundfor, Ivan Zaremba and Patrick Ottis; Villa D’Este announcer and columnist Simon Kidston; writer/photographer John Lamm; and knowledgeable enthusiasts/editors such as Jonathan Stein, Don Montgomery, Peter Larsen, Alan Boe, and many more.

If there’s a one-time featured class, like Facel-Vega or Pegaso, the judging team will consist of an experienced Pebble Beach judge and a marque expert or two. That’s a good way to become a judge, at least for that one time. Once you’ve had that experience, and if you have expertise in other brands, you may be asked to return in the future, if there’s a vacancy. The best advice is to watch the Pebble Beach announcements about what’s coming. If there’s a rare marque like Ruxton or DuPont coming up and you can prove your expertise, you might ask to be considered. People joke that someone has to die before a new person can be a judge at Pebble Beach, but that’s not really true. That said, there’s very little turnover. And there’s a long waiting list.

The Judges’ Meeting

The official judges’ meeting, on the Friday afternoon preceding the Concours, runs about two hours. It’s not mandatory but the discussions are always interesting. For new judges, it’s helpful to know the procedures and timing. If you’re an experienced Pebble Beach judge, you benefit from discussing topics like what constitutes over-restoration. Or how much of a car’s original bodywork must remain before points are deducted. And considering questions like, which period accessories are acceptable? When was metallic paint first used? How long after a car was built can the bodywork be changed, and will it still be eligible? And so on.

After 10 years of service, The Concours rewards judges with a commemorative pin in five-year intervals. Judges wear these proudly, like decorations on the chest of a service veteran. It’s a badge of honor. Every judge is a volunteer. If there’s anything that could be construed as a perk, it’s a posh Robert Talbot necktie that’s given to each judge each year, usually commemorating the featured marque from that year. They can choose to wear it that day or not.

Degrees of Perfect

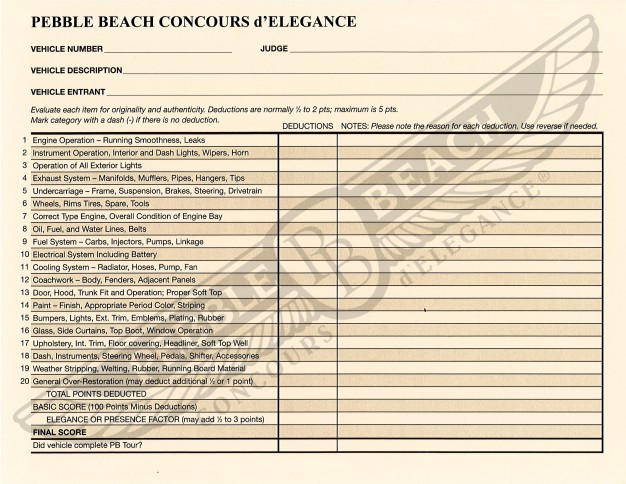

The comprehensive, 103-point judging sheet, derived from Classic Car Club of America criteria, has been carefully refined over the years. There’s a subjective factor of three points for elegance, presence, historic significance, color, etc., so a perfect 100-point car—and there are several of those each year—may be out-pointed by a 99-point example with better field presence, more sheer elegance, etc.

Historic significance, while not specifically judged, is an intangible that can help a car’s worth in some classes. For example, the Dean Batchelor Memorial Award, presented when there’s a biannual Historic Hot Rod Class, is given to the most significant car in the class. For 2015, it was awarded to the ex–Bob Hirohata 1951 Mercury owned by Jim and Sue McNiel.

“Pebble Beach is the toughest concours,” Paul Russell says. “The judges there are the most knowledgeable of any show. They’re judging technical authenticity, competence, style and elegance, compared to events where judging is purely subjective in the ‘French style.’ We don’t prepare a car any differently for Pebble, but we do mount a spirited defense for our authenticity choices. It starts with extensive research on each car. We make that into a book that we have on hand during judging.”

A Concours entrant, out on Highway 1 during the Tour d’Élégance.

The Pebble Beach Tour

Preparing a car for the Concours is hard enough, but then there’s the Pebble Beach Tour d’Élégance, a roughly 70-mile drive around the Monterey Peninsula that occurs the Thursday before the Concours. Anywhere from half to nearly all of the cars destined for the show field typically participate. There are no points for the Tour, but if two cars are tied in points and only one of them has completed the Tour, that car wins. “The Tour is a challenge, because we’re pretty much sticklers for authenticity,” says Russell. “We don’t use auxiliary fans or electric fuel pumps. So you might have a Ferrari that’s built to run well on open roads, stuck in a long line of traffic. But it’s a chance to see the cars dynamically, to hear them run, and that’s important.”

“The Tour is a grueling trip, a real test of the car,” says Mario Van Raay, whose RM Restoration cars have won Best of Show five times (including 2015), “but we try to encourage the owners to enter. It creates a lot more work for us, but we’ve never had a car fail. We are set up to help anybody’s car and we will if we’re needed.”

“I have mixed feelings about the Tour,” says Rich Fass, owner of Stone Barn Restorations and a past Best of Show–winning restorer. “But I think it’s something that should be done. You want the cars to run as good as they look. Customers feel they spent all this time and money getting the car ready, having it trucked out to California, getting it prepped, then you go on the Tour, and there’s more dirt and more cleaning. Each car is the best when it leaves the shop, so you’ve kind of wasted all that [preparation] time.” Stone Barn works with its customers to compensate. “When you leave my place,” Fass says, “the billing is finished. Now it’s up to the Judges.”

On the Show Field

On Concours Sunday, we start with another Judges’ meeting at 8:30 a.m., but this one is just to introduce everyone, have breakfast, and for Chris and Sandra to hand out the coveted long-service pins. Judges get their show folders, score sheets, and those neckties.

“Official” attire on Sunday is a blue blazer and tan slacks or a tan skirt. Most people wear straw hats. It can be cold in the early morning hours at Pebble but it warms up in the 80s before the day is over and the sun can be brutal. It’s only rained once in 65 years, so that’s not an issue.

About 350 people are on the field at 5 a.m. to watch the cars come in. Hagerty Insurance sponsors this popular “Dawn Patrol” event and distributes coffee, donuts, and commemorative hats. Meanwhile, on the lawn, owners are giving their cars final wipe-downs. We walk right to where our class is placed on the field, and we greet the Class Host, who’s there to round up owners and help with last-minute details. Then we walk the row of cars, not really judging, just seeing how they look and whether any car or cars just jump out. Then it’s time for business.

Pebble Beach judges doing their thing.

Judgment Time

If there are eight cars to be judged in the class, which is typical, we start at 9 a.m. sharp and allow about 20 minutes per car. We introduce ourselves to the owner or his representative—sometimes it’s the restorer himself—and ask how they obtained the car, what they know about its history, and what they did to the car: i.e. a full restoration, a partial redo, etc.

This is as much to help the owner relax as it is for our information. Most judges have done their homework already because the Chief Class Judge is allowed to let Class Judges access the application forms and photos filed online on the special Pebble Beach Judges’ website for their particular class. So we know the cars we’re going to see, we just don’t know how they will actually appear on the field.

For my classes, I always ensure my team has read this online material. In some cases, I have even gone to see a car while it’s in restoration. One year, I drove from Virginia to Baltimore to look at a historic hot rod. The owner was appreciative that I had gone to see his car, and he offered to pay me for my time and for travel expenses. I said that wasn’t necessary and that we weren’t allowed to be paid. He said, “I am a florist. Can I at least give you a bouquet for your wife?” I decided that was probably okay.

The official scoring sheet used by Pebble Beach judges

The 103-point judging form procedure mandates that we ask the owner to start the car and let it run for a few minutes. Once it’s started, one of us looks under the hood and under the car for leaks (sometimes a float sticks and a carburetor is dripping), another ensures all the instruments are operating, and we then check headlights and taillights, the brake lights, and, if installed, directional signals. If the car won’t start, we move on to the next car. The owner has until we finish judging that next car to get his car running. This year, one car’s horn didn’t work. That half-point deduction became critical when the final tallies were made.

It’s hard to get under a car when you’re wearing a blazer, a tie, and slacks, but I usually manage. People love to take photos when you’re bent over on the ground, as they think that such a thing never happens. They’re wrong—we do it all the time. Undeterred by onlookers, oblivious to them really, we carefully examine the engine, the exterior, and the interior, looking for paint flaws, blemished chrome, incorrect equipment—anything that’s not correct. We never touch a car, not even a door handle. We ask the owner or presenter to do that.

High Anxiety

Owners are often very anxious, even though they may be captains of industry. We try to put them at ease, but sometimes, they’re so nervous they can’t even get the key in the ignition.

Jay Leno likes to tell this story: “Years ago, a guy, who should remain nameless, had a car there. The judges came around with their clipboards. The car looks good. Oh! The clock is not working. The owner said, ‘Oh, um, let me get my restorer, okay?’ Now the owner is frantically looking; he can’t find the restorer. The judges say, ‘We’re going to have to deduct points because the clock doesn’t work.’ He goes, ‘No, no, hang on.’

“He runs off. He can’t find the restorer. So the judges say, ‘Tell you what, we’ll make our rounds. On the way back if you’ve got the clock running, we won’t deduct any points.’ He’s frantically looking all over for the restorer and can’t find the guy. Finally, the judges come back and the clock is still not working. They go, ‘Sorry, we’ve got to deduct two points.’ As the judges walk away, the owner sees the restorer, with a Coke in his hand and a sandwich, eating it. He starts screaming at the guy: ‘They dinged me and the clock doesn’t work!’ The restorer says, ‘Did youwind it?’

“That owner just assumed it was an electric clock. He didn’t even know.”

That’s not typical of every owner, but it’s pretty funny. (In reality, we’d deduct only half a point for an inoperative clock—but I’m not telling that to Jay.)

Jay Leno is a regular at Pebble Beach.

Keeping Score

My team and I carefully score each car against its individual judging sheet. The goal is to hurry without looking hurried. If owners have a restoration book with before and after pictures, we give it a look. Then we walk to one side, out of earshot of the owners, to do our deliberations. If we deduct, say, half a point for a slightly wrinkled convertible top, we make sure to be consistent with that deduction from one car to another, for the same penalty.

The entrants needn’t worry. We judge the car, not the owner or the restorer. And we don’t judge the trunks, so entrants have a place to store anything they bring on the field. If a car is a convertible, we judge it the way it’s presented. If the top is up, we judge the top. If not, we check to see that there is a top and proceed accordingly.

I act as scorekeeper, deducting a point or a half point where applicable, if a detail is incorrect, or if a component is not up to original standards. Over-restoration—excess plating or a polished part that should be unfinished or simply painted—is discouraged and penalized. A car can be painted a different color than it was originally, but the paint type must be correct for the period.

Tasteful vintage accessories, like Trippe spotlights, which are mounted on a bar with a bellcrank that lets the lights turn with the front wheels, are permitted on classics, but if a car is over-accessorized, it may lose a half point, a point, or more. We see a lot of Trippe lights on classics. Most are exact reproductions, and that’s permitted. But if every car in the classic era had been equipped with Trippe lights when it was new, the Trippe Manufacturing Company would still be in the automotive business. Radial tires in the correct size are permitted, but I have a preference (and that’s allowable) for the correct vintage tires. The same is true for halogen bulbs.

Upgrading to disc brakes, adding power steering, installing an electric fan (except in race cars which weren’t designed to be on a show field and run cool), modern Aeroquip fittings, incorrect modern brake lines, etc., are all frowned upon and you will lose points.

Cars must be clean but we don’t obsess about it. After all, many of the entrants drove in the Tour, and inevitably, the owner will miss some dust or the odd grease spot. That’s okay, as Ed Gilbertson, former Chief Judge liked to say, “Cars are meant to be driven; motorcycles are meant to be ridden.”

Get Off the Lawn! The Pebble Beach Tour d’Elegance Puts the Show Cars on the Road

And the Winner Is . . .

After we finish judging each car (and we do judge each car, even if an entrant is display-only), we sincerely thank the owner, then step away to double-check the deductions. We don’t add the scores and we don’t add any points—at this time—for presence, elegance, etc. That’s done after we’ve completed all the cars and we’re back in the judging room.

Owners and restorers watch our every move so we take copious notes as to why we’ve deducted points. “Pebble Beach judges know what they’re looking for,” says Rich Fass. “They key into every little aspect of the car. You have to be good to be invited out there in the first instance, so the judges have a very hard job, but they do a very good job of judging. As a restorer, I appreciate that.”

Finally, we check all the scores one more time, pick the first three winning cars (and a fourth in case one won’t start—they have to drive over the ramp to claim their trophy), and turn the forms in by noon. We’re treated to an elegant lunch in the Judges’ room while score sheets are reviewed and results officially tallied. Sometimes, Sandra Button or a member of the team that tallies the scores has a question, so we stay briefly after lunch, just in case.

Many times, like this year, it’s very, very close. Sometimes we have several cars with perfect 100-point scores, so it boils down to the subjective factor of the last three points.

For the 2015 concours, I judged historic Mercury customs, with restorer David Grant and hot rod racer and author, Don Montgomery. We three have judged together for many years, so we work very smoothly. We’ve had hot rod classes since 1997 in alternate years. This was the first time we’ve ever had Mercury customs on the show field, and it was a trip to see the chopped ex–Bob Hirohata and Fred Rowe Mercurys—cars that starred in classic B-movies like Running Wild with Mamie Van Doren—displayed on the same field as Delahayes and Duesenbergs.

With the results submitted, we’re then free to enjoy the show, and I like watching the cars being announced and crossing the ramp. Most people are good sports—after all, it’s an honor just to be on the field with your car. But we’ve had whiners, complainers, and even one disgruntled loser who trashed his room at The Lodge when he failed to win a trophy—but thankfully, that’s the exception.

As a Chief Class Judge, I have one vote for Best of Show and that has to be tallied after all the class winners are selected. As each first-in-class winner is named, the owner is directed to a special holding pen that’s set up near the oceanfront. When all the class winners are finalized, the Chief Class Judges and Honorary Judges are asked to walk down to that area and select the car they’ll nominate for Best of Show. After that’s done, I drop my ballot in the box and head to the Mercedes-Benz balcony for a glass of wine with my wife, Trish, and a bird’s-eye view of the last cars to cross the ramp.

The 2015 Pebble Beach Best of Show, a 1924 Isotta Fraschini.

The Moment of Truth

Best of Show is the big moment everyone’s waiting for. It’s always exciting, and while I’ve correctly picked the winners some years, I’ve also missed. The three or sometimes four finalists gather in their cars at the foot of the ramp. Everyone holds his breath. Who will win? Will it be prewar or postwar? Will the car start?

When Best of Show is announced, the runners-up stay in place and the winning car slowly drives over the ramp where the excitement quickly reaches fever pitch: Trumpets blare, cameras snap, confetti and streamers fly, and, more often than not, there are a few happy tears from the owner. The restorer breathes a sigh of relief.

“Best of Show is like winning the World Series,” says restorer Rich Fass. “The enthusiasm, the tears coming out of their eyes, it’s special. I want to be there every year, and I love the competition. When there’s only one winner, it means a lot to them, and it means a lot to me. There’s not another show in the world like it.”

In 2014, when John Shirley’s 1954 Ferrari 375MM Scaglietti Coupe became the first postwar car to win in decades, there was a lot of high-fiving on the balcony. The 2015 winner was Jim Patterson’s 1924 Isotta-Fraschini with body by Worblaufen, so you could say things have returned to normal at Pebble Beach. That is to say that the winner is an exotic marque from the prewar period with a custom-built body, in either coupe or roadster form, with a majestic grille, a long hood, a little cabin, and a flowing tail. This was Jim Patterson’s second Pebble Beach Best of Show win, but judging from his smile, it was just as exciting as the first time.

Jim and Dot Patterson and their winning 1924 Isotta Fraschini.

Our work as judges for the year is over, but the Selection Committee work begins again almost immediately. Each year always feels like a tough act to follow, but in an effort to help create the best Concours d’Élégance in the world, we’re always up for the task.

I love attending this event more than anything I do all year in the car world. I was surprised and honored to receive the Lorin Tryon Trophy in 2014—it’s the only award at Pebble Beach that’s given to a person, not to a car, and it’s for contributions to Pebble Beach and the old-car hobby. I was very proud.

And lastly, a confession that reveals how deeply I love this event: Some years ago, my brother called to say that he was remarrying; he had met his high-school sweetheart after decades had passed and they planned an August ceremony. When he told me the dates, I said, “Oh, Pete . . . it’s Pebble Beach weekend.” He said, “So just skip it one year.” I replied, “I can’t skip it.” Bless their hearts, they changed the date of their wedding.

There’s only one place I’d rather be in the third week of August, and now you know why.

Author Ken Gross has been a judge at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Élégance for more than 25 years. He’s written more than half a dozen automotive books and has placed articles in magazines ranging from Playboy to Road & Track. A few prewar Fords highlight his personal car collection.