Octane Magazine, April 2010

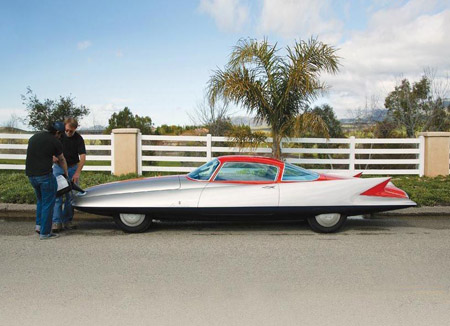

It never ran in period but now an American enthusiast has breathed life into Ghia’s 1955 dream car Gilda…

‘I just hate pushing cars at car shows’ is the reason Scott Grundfor gives for breathing life into the Ghia Gilda, more than 50 years after it was created. A good enough reason for motorising it, you might think – but to search out and install a 1950s gas turbine engine was surely going slightly over the top?

In 2009 the restored Gilda – officially called the Ghia Streamline X but known as Gilda ever since it was built, after the raunchy character played by Rita Hayworth in the 1946 film of the same name – wowed the crowds at Villa d’Este and Pebble Beach as it whined and howled its way before the podiums. Looking every inch the 1950s ‘dream car’, its Jetsons styling combined with the jet-engine roar of its AiResearch turbine to make it an instant show-stopper. Ironically, when built in 1955 Gilda didn’t have an engine of any kind, let alone a gas turbine, but it seems likely that a turbine was intended for it.

Scott, who runs a Californian restoration shop, already had a small collection of Ghia-built prototypes when Gilda came up for sale by RM Auctions in 2005. Scott hadn’t been actively pursuing Gilda but realised he just had to have it:

‘Maybe it was sales patter, I don’t know, but there was a rumour that if the car didn’t sell it would be turned into a table for RM’s new boardroom! It’s been named as one of the ten most significant show cars by Strother MacMinn, who was a hugely influential lecturer at the Art Center here in California, and it’s a proper ‘dream car’ of the kind I saw when I was a kid and my grandfather would take me to motor shows. In the 1960s the dream cars gave way to concept cars, and then to so-called special editions, but Gilda was from that time when show cars really were visions of the future.’

Gilda’s exposure on the show circuit was a brief one. After debuting at the 1955 Turin Salon – and attracting worldwide press attention – it was donated to the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, where it stayed until 1969. Then it had lengthy spells in the Harrah and Blackhawk Collections, until it became surplus to requirements in 2005. In all that time – 50 years – Gilda never once moved under its own power.

Scott claims that he really did decide to motorise Gilda because he knew he’d have no incentive to take it to car shows it if had to be pushed around every time it was loaded and unloaded. But the decision to modify a totally original vehicle was not an easy one for this restorer to whom conservation is everything. ‘As my friend the automotive writer Michael Lamm said, “If you do it, you mustn’t f*ck it up!”’ In fact, the installation of the AiResearch gas turbine involved remarkably few changes to the car.

Certainly, contemporary press reports assumed that Gilda was a future turbine car, with magazines such as Motor Trend and Road & Track baldly stating as such. In 1955, when Gilda was built by the Ghia craftsmen in Turin, gas turbines were widely seen as being the Next Big Thing in car technology. Jet engines were transforming the world of aviation and no-one in the motor industry wanted to be left behind. Ironically, it was arch-conservative Rover who had first demonstrated the potential of the gas turbine when its JET 1 prototype – based on the staid Rover P4 ‘Cyclops’ saloon – scorched to 152.9 mph in 1952.

Within a couple of years several major manufacturers were riding the gas turbine bandwagon, among them Chrysler, whose cars had a reputation for being well engineered but unexciting. A gas turbine was fitted to a porridgy Plymouth Belvedere in 1953 and more advanced prototypes quickly followed. Other companies such as Fiat and Renault produced turbine cars of their own, and even Austin got in on the act by shoehorning a turbine into an Austin Sheerline (if you find this hard to believe, visit Austin Memories on the web).

But why all the interest in gas turbines? Compact power, and the ability to run on pretty much anything that will burn, are the short answers. A gas turbine is much like a jet engine except that, instead of the gases physically pushing the vehicle along, they spin turbine wheels that can be geared down to drive road wheels. It’s ready to go from the moment you switch it on, with no warm-up time, and it remains virtually maintenance free in operation because there are no internal combustion by-products to contaminate its lubrication.

The downsides are heavy fuel consumption and a lot of heat, most of which (on the early gas turbines, at least) was simply lost to the atmosphere. And to the legs of any unwary bystander who happened to be standing directly behind the exhaust. But in the 1950s these problems did not seem insurmountable, and rapid progress was being made to cope with them.

At about the time that Chrysler was dabbling with its first gas turbines, Virgil Exner was made head of design and he quickly struck up a mutually beneficial relationship with Ghia. It wasn’t Ghia’s design capability that Exner needed – the Torinese company was actually putting out some pretty hideous stuff in the early ’50s – but its facilities for building high-quality one-offs. Ghia also had access to the wind tunnel at Turin’s Polytechnic, which Scott Grundfor believes was a crucial factor in the Chrysler connection. Gilda, with its aerodynamic body and long tail fins, was, he thinks, nothing less than a testbed for Chrysler’s forthcoming ‘Forward Look’ – the Look that kick-started the tailfin wars with GM in the late ’50s.

Gilda does have a lot of similarities with the 1956 Chrysler Dart that was commissioned from Ghia by Exner. The Dart was a much bigger car, equivalent to a full-size American sedan, but Scott is convinced that Gilda was was also sponsored by Chrysler. He recalls Exner’s son, Virgil Exner Jr, explicitly telling him that in a conversation some years ago, when Exner Jr also revealed that Chrysler had shared aerodynamic test data from its wind tunnel research centre in Detroit.

‘Once the hemis came out, Chrysler started getting worried about the cars getting squirrelly at really high speeds,’ explains Scott. ‘Exner published a paper in 1957 explaining the aerodynamic advantages of tail fins. There’s still some debate about whether the fins were really just a styling exercise, but I’m convinced Gilda looks the way it does as a result of the wind tunnel testing.’

Significantly, the man in charge of the Gilda project was Giovanni Savonuzzi, who was an aerodynamicist and engineer rather than a stylist. As a young technical graduate he worked with Fiat’s aircraft division during WW2 – where he helped develop turbines – before joining Cisitalia post-war and shaping the Aerodinamica coupés. He moved to Ghia in 1954; three years later he was made head of Chrysler’s turbine division, where he would develop the successful 1963 turbine cars. During those three years at Ghia he oversaw some of the company’s most attractive and dramatic designs but his daughter Alberta (who moved with her father to the USA in the late 1950s) says that he never took much credit for his work.

‘He had no interest whatsoever in self-promotion,’ says Alberta. ‘He used to say, “The people I care about – they know.” My father was a very complex man, to whom mathematics were an art and who had an eye for beauty in all its forms. That included beautiful women, of course, but in a respectful way. He admired Rita Hayworth because she was a beautiful woman, and always maintained that it was he who came up with the name Gilda for the Ghia car.’

Giovanni Savonuzzi died in 1986 but the resurgence of Gilda seems to have helped revive his reputation – Alberta hopes there will be an exhibition in 2011 to mark the centenary of his birth. Public awareness of Savonuzzi has surely been increased thanks to Scott’s installation of a period-correct turbine in Gilda, which has given this dream car the vital ingredient of motion it’s always lacked.

‘I found the turbine on eBay!’ says Scott. ‘It’s very similar to one shown in a September 1955 aviation magazine, and would typically have been used to power a generator or starter motor; anything that needed a compact, high-performance power unit. It puts out about 70bhp but with the right gearing it could possibly push Gilda up to 150mph – a friend has put a similar engine into a Honda CRX, which is less aerodynamic, and that’s been clocked at 90mph. Devising a transmission for Gilda required a lot of thought but we came up with what I think is quite an elegant and lightweight solution.

‘The turbine spins an output shaft at 54,000rpm that is geared down to drive a small hydrostatic transmission at 2700rpm. Basically, the hydrostatic transmission consists of two pumps, one pumping fluid in and one out, with a movable “swash plate” inbetween that regulates the amount and direction of the fluid flow. The plate can be adjusted by moving the T-bar in the cockpit to give forward, neutral and reverse, so there are no gears, just an infinitely variable power delivery. Because the gearbox only weighs 60lb and the engine about 100lb, it’s quite a light package altogether.’

Chrysler famously claimed that its 1963 turbine car would run on anything from peanut oil to Chanel No 5, and it’s true that turbines will happily consume anything you can set fire to. Scott has found that jet aviation fuel burns relatively cleanly, but the turbine can equally well run on kerosene, gasoline, diesel or heavy oil. That was another reason the car companies were so interested in the 1950s – you didn’t need expensively refined petroleum. If you’re a conspiracy theorist, it may also explain why the oil companies were less keen…

Firing up Gilda’s turbine is simplicity yourself. You turn on the ignition, which switches on a pump to pressurise the fuel, operates a solenoid to let it flow, and starts the igniters clicking away – just like the one on the gas fire in your gran’s front room. Then a small electric starter motor spins the turbine compressor up to about 27,000rpm. The fuel ignites at about 15,000rpm and that’s frankly a pretty scary moment, because that’s when a 747-style roar erupts behind your head and suddenly rams home the fact that you’re sitting in front of a jet engine and only shielded by some 1/8in aluminium.

Turbines don’t ‘do’ slow idle speeds so the noise is constant, and loud. Loud enough that driver and passenger have to shout at each other; but also loud in a kind of test pilot way that makes you feel like Nigel Patrick about to go for the sound barrier in the eponymous 1952 movie.

Which is ironic, because Gilda is actually restricted to little more than 30mph for safety reasons. That’s not just because the engine is 50 years old, and Scott isn’t keen on having fragments of turbine blade whistling past his ears, but also because Gilda’s suspension is near solid – in fact, it is solid at the rear. This car was, after all, never expected to cover a more demanding surface than the linoleum in an exhibition hall, so chassis dynamics were hardly a priority. Scott has, however, replaced the original CEAT skinny tyres as a gesture towards road safety.

Not that there aren’t still hazards when driving Gilda, of course. ‘The only way to shut the engine down is to cut off the fuel supply,’ Scott explains. ‘So I’m not sure quite what you’d do if the solenoid failed that controls it…’ In fact, Gilda nearly claimed one celebrity scalp while manoeuvring at a car show last year, when it refused to cease forward (albeit very slow speed) motion and almost ran down George Barris, of custom car fame. What a bizarre accident report that would have made.

Fact is, though, that Gilda works and works well, effortlessly shunting back and forth during our photo session and always firing up straightaway when called upon to do so. Scott professes that he has no desire to make Gilda go faster: that would involve too much redesigning of a car that is remarkably original.

But by coincidence, just a few days after Octane’s ride in Gilda, we were treated to another ride in another gas turbine car. Jay Leno recently acquired one of the nine surviving 1963 Chrysler turbine cars and it’s in perfect working order. To prove it, he took us out into the maelstrom of a Los Angeles freeway. Whooshing along at 65-70mph it was quiet, comfortable and refined: everything that the turbine pioneers of a decade earlier could have wished for.

It’s not perfect, though. Like the Wankel rotary, the turbine is not an especially fuel-efficient design. Which is why, sadly, the dream of turbine cars is likely to remain just that – a dream.