Original Article – Aug 13, 2015 – New York Times

A Ferrari Superamerica Coupe thought to be the only of its kind built with an alloy body. It is the same, inside and out, as when it left the showroom. CreditOscar Hidalgo for The New York Times

On Sunday, a rare Ferrari will take its place among a special group of cars at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, there to be admired by the world’s most discerning car collectors.

Unlike the majority of the restored classics on display at the Pebble Beach Golf Links in California, however, this 400 Superamerica Coupe remains largely untouched from the day it left an Italian dealership some five decades ago.

The Ferrari is a dazzling example of an emerging kind of vintage car, where original condition, even with flaws in paint and upholstery, is valued over pristine restoration.

And the market is following. For the first time, the Pebble Beach show, among the world’s most prestigious, will feature a separate preservation class for vintage Ferraris.

“Because this preservation class is happening at Pebble — and because these are Ferraris — the significance is huge,” said David Gooding, president of the Santa Monica, Calif.-based auction company that bears his name. “It shows how much our ideas are changing about what a classic car should look like, how it should be maintained and repaired, and what it is worth.”

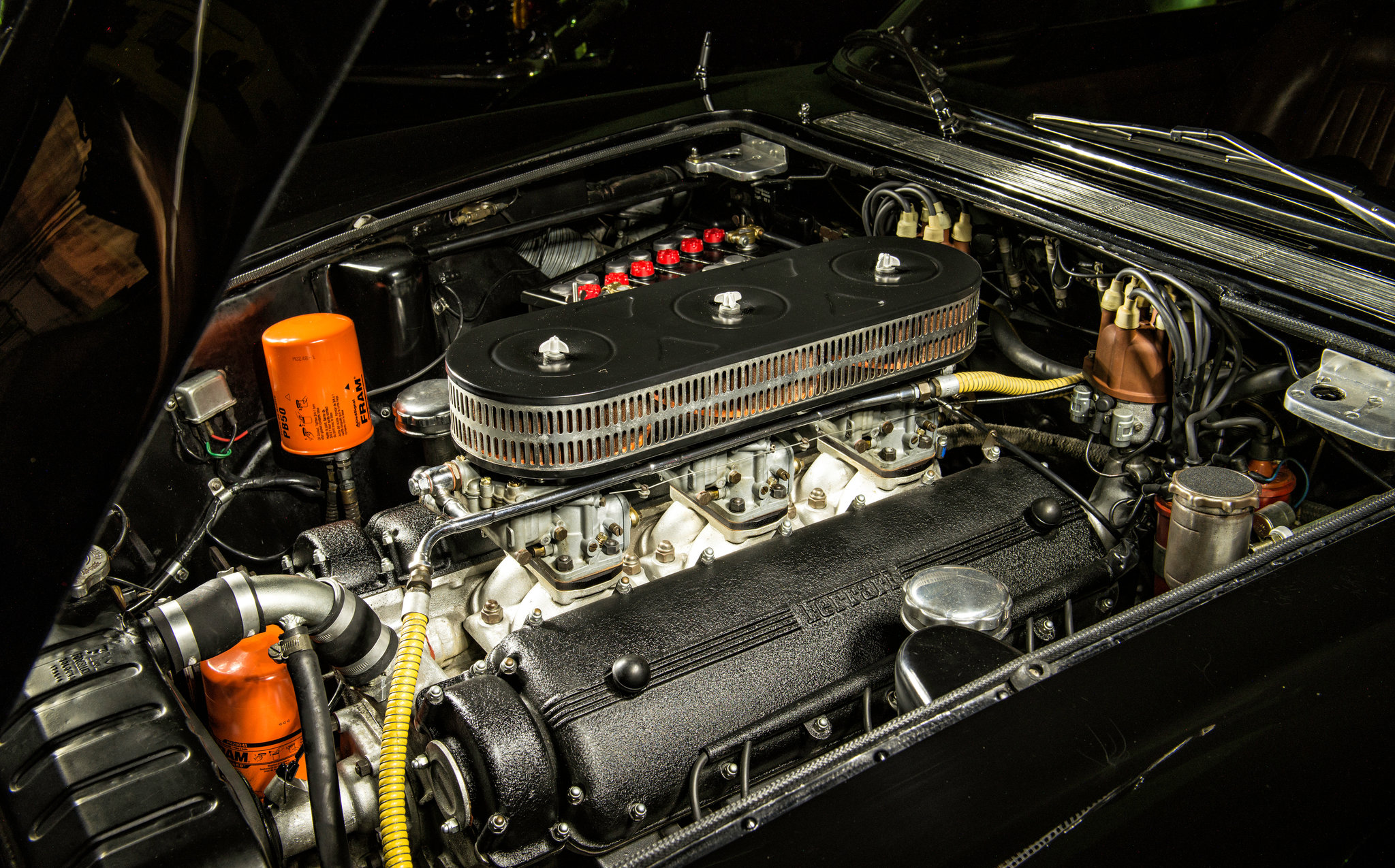

The engine of the Ferrari 400 Superamerica. CreditOscar Hidalgo for The New York Times

At stake are auction prices in the millions. Last year, sales during the eight-day gathering of vintage cars in and around the Monterey Peninsula hit a record $399 million. They included a world record single-car price of $38.1 million, for a 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO.

Mr. Gooding says he believes the tipping point may have come at his company’s January 2014 auctions in Scottsdale, Ariz. Two virtually identical 1956 Mercedes 300SL Gullwing coupes, both painted black with red leather interiors, were on offer. But any similarity ended there.

“It was like beauty and the beast,” Mr. Gooding said. “One car was perfectly restored — a 100-point example that ran superbly.” The other was an untouched — and quite filthy — barn find, he said, with a sagging headliner, torn seats and “rats’ nests under the hood.”

The ugly duckling sold for just under $1.9 million, nearly $500,000 more than its twin.

A month later, an unrestored 1964 Shelby Cobra Daytona Coupe, owned by the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum in Philadelphia, became the first automobile to be included in a new federal registry of historic vehicles, similar to the National Registry of Historic Places.

“Restoring cars is not an evil thing — when they need it,” Sandra Button, head of the Pebble Beach concourse, said in a recent interview. But, she added, “I hear from collectors all the time who say, ‘I restored my car 15 years ago, and I wouldn’t do it now.’”

Ed Gilbertson, former chief judge at Pebble Beach and a current member of the show’s selection committee, compares the trend toward preservation in classic automobiles with antique furniture, where excessive refinishing has long been regarded as an enemy of value.

John Mozart of Los Altos Hills, Calif., a longtime collector whose competition-scarred 1966 Ferrari racing coupe was also chosen for the preservation class, said that enthusiasts became too caught up in vehicular cosmetics. “When I started, the only reason people bought old cars was to restore them.”

The Ferrari’s owner, Dr. Richard Workman of Windermere, Fla., says that when he bought the car, it was completely original, the same inside and out as when it left the showroom.CreditOscar Hidalgo for The New York Times

Indeed, that was the intended fate for the Superamerica Coupe, acquired in the spring by Dr. Rick Workman, a dentist from Windermere, Fla., for “slightly above” its $4 million market price.

Dr. Workman and Tom Hill, his restorer, set about examining the vehicle, one of only seven models of its type. Although they knew the same Italian family — headed by a friend of Enzo Ferrari — had housed the auto in a climate-controlled garage for more than four decades, “We assumed we’d be redoing it to make it perfect,” Dr. Workman said. “We hadn’t really been looking for an unrestored car.”

The men soon realized that the glistening black Ferrari was completely original — the same, inside and out, as when it left the showroom. Rather than planning its restoration, they decided to use a special dry ice cleaning process that removes oil, dust and dirt without disturbing original surfaces.

Afterward, they made another discovery, one Dr. Workman called “a Eureka moment.” On the underside of the left front fender, Mr. Hill spotted something they had never expected to see on what was assumed to be a steel-body car: a patch of bare aluminum. Further tests with magnets and a review of factory archives confirmed the Ferrari was even rarer and more valuable than they’d thought. Indeed, Dr. Workman says he believes it is the only Superamerica built with an alloy body.

“We’re learning,” Dr. Workman said, “that it can be equally pleasing to see a car that has been loved and nurtured for 50 years as one that has had a nut-and-bolt restoration.”

Many enthusiasts treasure historically significant automobiles for their artistry, innovation and craftsmanship, to be cherished much like fine paintings or sculpture.

“What we’ve been doing to these vehicles would be an abomination in those fields,” Scott Grundfor, a restorer, says. “Restoration came to mean the complete destruction of all original surfaces.”

A frequent Pebble Beach judge, Mr. Grundfor, of Arroyo Grande, Calif., is preparing a 1967 Ferrari for the preservation class. “I want it to be a demonstration project that encourages people to stop restoring cars unnecessarily,” he said.

Owned by an ardent preservationist, Evan Metropoulos of Los Angeles, the car, a Pininfarina convertible, had a serious engine fire in 1969. Shunned by investors and collectors, it sat in storage where residue from smoke and flame-extinguishing chemicals caused further damage.

The Ferrari 400 Superamerica Coupe, in the garage. CreditOscar Hidalgo for The New York Times

At Mr. Metropoulos’s behest, rather than stripping the car to bare metal as with a typical restoration, Mr. Grundfor and his team revived damaged paint surfaces with cleaners and fine-grit sandpaper. Rather than replating smoke-caked window frames, the metal was cleaned with soap and water.

Faced with some dents and a badly etched rear deck, however, Mr. Grundfor opted for an artist’s airbrush, delicately blending such areas with original paint. Repairing minor damage, but not repainting the entire vehicle, he approximated what would have been prudent care by an original owner.

Mr. Grundfor’s decision illustrates the gray areas confronting preservationists. When can a repair or modification — for example, a new radiator core that permits an old vehicle to be driven in modern traffic — be made without detracting from the car’s originality? When should a damaged body panel receive fresh paint? As he acknowledges, “Preservation has yet to be fully defined by a body of written rules.”

Mr. Mozart affectionately traces a noticeable fender dent in his Ferrari, one of the company’s last grand touring coupes built for racing. “How far do you go with this?” he said. “We know the air in the tires isn’t original, and that all rubber rots. At some point practicality and usefulness trump originality.”

Most preservationists agree that classic cars should be driven. “A car that doesn’t run is a statue,” says Frederick Simeone, founder of the Philadelphia museum. “Its integrity as a vehicle is lost.” The museum rotates its collection of racing sports cars through regular demonstration runs.

Restored vehicles will continue to reign at shows like Pebble, if only because, for better or worse, so many historically significant cars already are restored. That leaves preservationists scrambling for a shrinking pool of original cars.

Of course, the ultimate evidence of preservation’s rise will be when an unrestored classic takes the Best of Show award.

On a lawn of shining, spotless dream cars, could such an automotive Cinderella really stand a chance?

“Absolutely,” Ms. Button of the Pebble Beach concours said. “By offering owners a place to participate and compete, we want to encourage them not to restore vintage cars needlessly. And if they’re unsure, to let them be.”

Update: The Ferrari Superamerica owned by Dr. Rick Workman came in second place in the Ferrari Preservation class at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. A 1964 Ferrari 250 GTL Scaglietti Berlinetta Lusso placed first.