Today, starting a new Mercedes-Benz dealership requires a multimillion dollar investment, but this wasn’t always the case. In the 1960s a technically qualified individual could become a dealer on a shoestring. Among those who did so was Bert Reimschuessel.

In 1965, when Daimler-Benz reacquired the rights to sell and service Mercedes-Benz vehicles in the U.S. from Studebaker-Packard, they faced the problem of setting up an entirely new dealer network. Certainly Daimler-Benz would have preferred to establish luxurious dealerships in convenient downtown storefront locations with a full service department, a pleasant sales area, and a well-stocked parts department. Still, in many areas, especially outlying towns, that just wasn’t possible. Daimler-Benz wanted good geographic coverage and the maximum number of dealers, so to get things rolling the company was willing to issue franchises to small service/parts dealerships, some of which sold very few new cars at all.

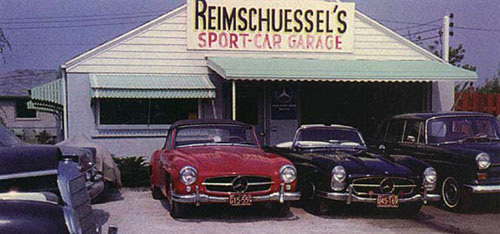

Established as an independent shop in 1958 by Bert Reimschuessel in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, Reimschuessel’s Sport Car Garage became such a dealership.

German-American

Bert had started his automotive odyssey in Germany before World War II. At the Daimler-Benz factory he trained for several years as an apprentice then as a mechanic. He worked there until the war, when he was recruited into the German army. During the war he worked on many projects, one involving the design and construction of a remote control tank. After the war he got a job with Ford in Germany building Taunus cars; he quickly became a supervisor in the mechanical service department, where he oversaw 45 other mechanics. Life in Germany was difficult then. Resources were scarce, living was hard, everything was expensive; the quality of life wasn’t very good. Many parts of Germany had been literally leveled, and the country was busy surviving, digging its way out of the rubble.

Bert had an acquaintance in Wisconsin, which had a large German community, and he saved enough money to immigrate to the United States in 1956. His first U.S. job was in a Chevrolet dealership in Manitowoc, 70 miles north of Milwaukee. There was still considerable postwar prejudice against Germans, and since Bert didn’t speak English very well, he was given a low-status job, essentially washing cars and sweeping up. Little by little he took advantage of opportunities to help the mechanics, and they quickly realized that he was highly qualified and hard working. Eventually he earned a position as repairman in the service department.

In 1958, Bert had the chance to open his own shop, servicing foreign sports cars as well as American cars. It started as a two-person operation: Bert plus his faithful secretary Grace Gadzinski. Bert dealt with the cars while Grace handled the bookkeeping, answered the phones, and made appointments. At first this downtown business, which he called Reimschuessel’s Sport Car Garage, would take in almost any job just to keep the doors open. Bert quickly earned a reputation as a first-rate mechanic and became very busy. For the next few years he built a successful business doing general service work. Grace’s son Steve joined them and eventually worked for 23 years as the parts man. The shop was small—maybe 2,000 sq ft—but it was efficiently organized, maximizing Bert’s ability to work in such a limited space.

Usually an assistant worked with Bert in the shop, but Bert was a perfectionist, difficult to work for, so these helpers came and went. According to one of them, “Bert had eyes in the back of his head. If you didn’t have exactly the right tool in your hand, he’d notice it and come unglued.”

Bert always had a special interest in racing. From the time he opened his shop, he prepared sports cars for Sports Car Club of America races, often at Road America at Elkhart Lake. Several of his clients were avid racers; he had a 300SL Roadster himself, and an Alfa Romeo 1600 Guilietta Veloce Spider, both of which he raced. Photos of his race cars and those of the factory adorned the shop’s crowded walls. Besides being an expert on Mercedes-Benz, he was known for repairing Porsches, Volkswagens, and other sports and European cars. He was equipped with technical information and experience on all sports cars. A neighbor said that during the racing season it was common to see the shop open all hours of the night, with race cars lined up for testing and tuning. One night a Porsche factory transporter pulled up with a load of RSK Spyders going to a race at Elkhart Lake. They wanted Bert to tune them for peak performance on the dynamometer.

Service-Only Dealership

When Studebaker-Packard returned the Mercedes-Benz sales and service franchise to Daimler-Benz, Bert saw the opportunity to join Mercedes-Benz again. Besides his knowledge, shop, and tools, to be considered for a dealership he had to present Mercedes-Benz of North America with 30 trade references stating that he was qualified and an upstanding person. It’s unclear how many of these one-man service dealerships were set up, but today only a handful remain in the U.S.

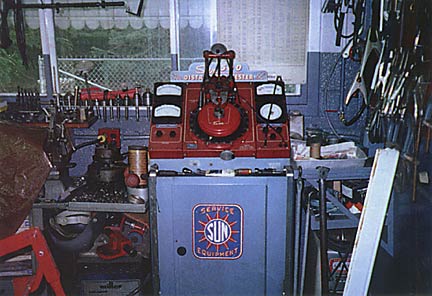

As a Mercedes-Benz dealer, Bert was privy to all the workshop manuals, service bulletins, parts books, owners’ manuals, service microfiche, special tool catalogs, and special tools that only dealers would have. he owned almost every conceivable repair and test tool, including a chassis dynamometer.

Until 1993, when failing health finally forced him to stop work, Bert labored 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, repairing Mercedes-Benz cars almost exclusively and earning a reputation as one of the finest mechanics in the country. In fact, when the Mercedes-Benz district office in Chicago occasionally had a particularly difficult repair problem, they would send the customer up to Bert to seek his advice and have him deal with it.

Mother Lode, a Treasury of Tools

In July 1997 I got a call from Tony Rotherie, an automotive broker from Milwaukee. He mentioned that a small Mercedes-Benz dealership in nearby Manitowoc, Wisconsin, was being sold to settle an estate. As he listed some of the equipment, parts, and literature, I realized that it comprised a 40-year time capsule of Mercedes-Benz technical information, special tools, and equipment. He mentioned that the collection was “somewhat” extensive. For example, he had made a cursory count of screwdrivers—all 600 of them! He asked if I might have an interest. Being a Mercedes-Benz historian and restorer as well as a tool junkie, I replied affirmatively.

When I visited Reimschuessel’s with Tony, I wasn’t quite prepared for what I saw. As an automotive restorer, I’ve visited many other restoration and repair shops, have been around tools and equipment all my life, and have visited the factory workshops in Stuttgart. But walking into this tiny shop’s repair area, where much of the equipment was stored, I was completely unprepared for the sheer mass of tools, equipment, and technical information that Bert had accumulated during his 40 years of business. I was humbled.

Arrayed around me were literally thousands of specialized pieces of equipment and tools designed, specified, and sold by Daimler-Benz to test and repair its vehicles. The equipment spanned a period from the late 1940s to the early 1990s. Apparently Bert had a strong penchant for having exactly the right tool for every single repair he ever performed. Over 40 years in business he had collected an enormous number of special tools. He insisted on only the best—Snapon, Stahlwille, Hunger, Bosch, Sun Equipment, Hunter, and Robinaire, to name just a few.

In his microfiche files I found technical manuals and parts information to repair every Mercedes-Benz model from 1949 through 1995. What’s more, Bert had rarely if ever thrown anything away. If he bought a more modern tool—a better engine analyzer, for example—he carefully wrapped up his old piece of equipment, often in the original box which he had saved, and stored it in the attic. Preserved in this fashion was some of the earliest equipment that he had when he came over from Germany in the 1950s.

Bert maintained enough equipment to do everything in-house except major machine work. Besides the regular tools and equipment, he even had tools to test the tools — devices to test the calibration and settings of the special tools. There must have been 30 or 40 different types of torque wrenches plus a special tool to test torque wrenches. His is the most complete collection of MercedesBenz technical information and literature, special tools, and equipment I have ever seen. It’s a pleasure to share it with you now.