The 1955 300SLS Prototype

By Dennis Adler

This,

1955 300SLS Prototype

sleek, light metallic blue roadster has been determined to be chassis 00009/52, one of eight 300SL prototype coupes raced by Mercedes-Benz in 1952. From there it became the prototype for the 300SL Roadster and finally assumed a third role as a mule for the factory’s 300SLS race team in 1957.

Prototypes serve as test cars for new ideas, engineering technology, and designs. Most end up as scrap, but occasionally one is found on flaccid tires, fading away in a dusty, shuttered garage, whereupon aficionados immediately elevate it from ancient junk to treasured artifact, as if a sealed chamber had been opened to reveal the relics of an extinct civilization. Usually what is uncovered is the skeleton of a failed project, a curiosity at best. Once in a great vvhile, though, an opening door reveals the unexpected, a true prototype, the first example of a genuine success story. If that is rare, then finding a car that has served as a factory prototype three times over is remarkable.

Born in 1952

After watching from the sidelines as Jaguar C-Types handily captured the 24 Hours of Le Mans in June 1951, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, DBAG’s passenger car development chief, decided it was time for the silver arrows to restake a claim on international sports car racing.

The C-Types that so impressed Uhlenhaut were developed from Jaguar’s XK 120 sports cars. Unfortunately DBAG had no similar starting point. With chief design engineer Fritz Nallinger, Uhlenhaut thus set about developing a new lightweight sports car based on the 300 sedan. Using the 300’s six-cylinder engine and much of the car’s drivetrain and suspension, the first 300SL prototype was completed and tested on February 15th, 1952, a mere eight months after Uhlenhaut had conceived the project.

The first ready-to-race 300SL was presented to the press that March, and in May, Karl Kling, driving the 00004/52 prototype coupe, finished second to Ciovanni Bracco’s Ferrari in the most grueling of all European motor races, the Mille Miglia. This auspicious first outing was followed by a 1-2-3 sweep at Berne and a stunning 1-2 at Le Mans in June.

At Le Mans, 00009/52’s first race, Theo Helfrich and Norbert Niedermayer finished second to Hermann Lang and Fritz Reiss in a similar coupe. After the race, four coupes were rebodied into lighter roadsters for that August’s Nurburgring sports car race, where Riess drove 00009/52 to third place behind two other roadsters. The car’s final race was the formidable Carrera Panamericana in November. With American John Fitch at the wheel and Eugen Geiger as mechanic, it vvas disqualified due to a technical infraction. No matter, for the coupes of Kling/Klenk and Lang/Grupp finished 1-2.

By then 300SL’s had either won or finished second in every major race they had entered, a remarkable achievement considering that just 11 months earlier the cars didn’t even exist and that Daimler-Benz hadn’t built a racing car since the late 1930’s!

After 1952 the SL’s were withdrawn from competition, allowing the engineering department to concentrate on designing an all-new Grand Prix race car for 1954. During this period a few of the SL racers were returned to engineering, where they were used to test and evaluate new designs. For instance, 00009/52 was used for carburetor tests on the Grossglockner pass.

A Second Life

After 300SL coupe production began in 1954, one Panamericana chassis, this car, was used as a prototype for the 300SL Roadster. Chassis 00009/52 had entered its second life.

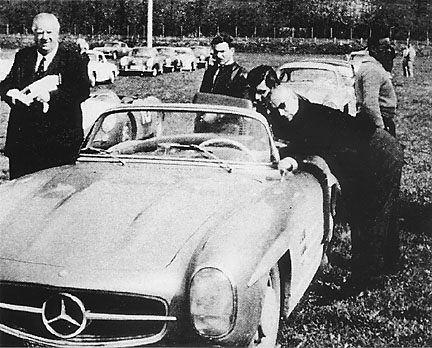

Along with several other prototypes, 00009/52 is believed to have been shown to the DBAG board of directors at their meeting on November 2nd, 1955. It was then used for publicity purposes, and in the summer of 1956 became the subject of a pictorial essay by famed photojournalist David Douglas Duncan that appeared in the October 12th, 1956 issue of Collier’s magazine.

In an article entitled The Secret SLS, Duncan detailed his visit to Germany and Switzerland, where he photographed the new sports car being tested by designer Karl Wilfert. Duncan wrote, “Though much technical data is still cloaked in secrecy, factory officials have released enough details with these exclusive Collier’s photos to give a clear idea of what that streaking shape actually is when standing still…a giant two-seater convertible roadster combining features of Mercedes’ revolutionary gullwing-doored 300SL coupe and the streamlined racer in which Juan Manuel Fangio of Argentina beat the world on the Grand Prix circuit, the World Series of professional racing. The SLS (Super Light Special) clears the ground by a hand and stands but 33 inches high at the door cowling— lower than the ears of the police dogs assigned to guard it. Designed by racing experts for sportsmen to whom the final product is the only consideration, the 300SLS is unlikely to become the second car in every man’s garage. It is meant to be the crown jewel among all sports cars…”

A Third Life

Although DBAG had officially withdrawn from racing in 1955, Daimler-Benz of North America urged Stuttgart to enter the new Roadster in Sports Car Club of America races for 1957, coinciding with the introduction of the 300SL Roadster. Our subject car, already described as an SLS to Duncan by the factory, served as the prototype for two newer, lighter, and more powerful SLS cars.

On December 20th, 1956, Uhlenhaut ordered two new SLS racers built on the single-point swing-axle chassis. Completed by April 1957, they were prepared by Alfred Neubauer’s sports department and shipped, with this car, to America. With factory mechanics in support and a team organized by George Tilp in New Jersey, U.S. driver Paul O’Shea took the SLS roadsters into SCCA competition.

Then in its third life, 00009/52 was the team’s test car, fitted with various windscreens, wheels, tires, etc. Because it was heavier than the two new SLS models, and since it also had the original, less responsive (perhaps too responsive) gullwing-type swing-axle, it was not raced. When the 1957 season concluded, O’Shea and Tilp had given DBNA exactly what it wanted, the Class D SCCA Championship. The production 300SL Roadster became the crown jewel of American sports car enthusiasts. After 1957, 00009/52 returned to Stuttgart. The two SLS racers were reportedly sold in the U.S. for $56,000 apiece. Then they vanished, and their whereabouts remain unknown to this day. (In case you’re looking, their chassis numbers were 8467198106/2 and 8442620070/1.)

Back to America

According to research conducted at the Mercedes-Benz archives in Stuttgart, DBAG kept 00009/52 until 1965. Originally equipped with the M194 carbureted engine in 1952, the factory fitted the car with the fuel-injected M19X motor in 1953. That was how O’Shea got it in 1957, and that was how it was sold to Karl Jurgen Britsche of Hamburg, Germany, in 1965. Paperwork with the car stated, “The 300SL roadster was a continuation of the Type SL coupe and had the same designation 300 sports light roadster. This was a prototype car.”

Some years later Britsche sold the car to Arthur von Windheim, also of Hamburg, then in 1980 American collector and dealer Lloyd Ikerd purchased it and brought it back to the U.S. Seven years later, noted Mercedes-Benz restorer Scott Grundfor, of Scott Restorations, bought the prototvpe and hegan a complete restoration on what was then a car in pieces, boxes, and bags. “It was all there,” rccalls Grundfor, “and we knew it was something special.”

According to John Ling of Scott Restorations, this 300SLS prototype is the very first 300SL Roadster. Ling points out that it retains many parts used on the race cars—the magnesium intake manifold, magnesium oil pan, and drilled-out, lightweight suspension. As a test car it was fitted with early-style Dunlop front disc brakes. A virtual hybrid today, combining parts from all of its three lives, the car retains the original Panamericana racing suspension, fuel-injected engine, and countless 300SL Roadster prototype components. Its one-piece glass headlamps are the original prototype parts.

In 1955, DBAG had not settled on all of the interior details for the Roadster, and many designs on this car never went into production. The dished, wood-rimmed steering wheel, the indirect interior lighting, and an innovative ashtray and lighter were all left off production Roadsters. The seats were a cross between the coupe’s and the Roadster’s. As for the windows, they came and went. They were on the car when it was photographed by Duncan in 1956 but removed when O’Shea had it in 1957 and never replaced, even when the car was restored.

At a glance this may look like a 300SL Roadster, but its body is shaped quite differently from the production version. The front fenders and grille opening are more pronounced, giving this SL an aggressive, almost Ferrari-like appearance. The grille design is also unusual. The trim has a predominant lower lip projecting beyond the body, and the concave barrel star in the center is from an early 300SL coupe. The early coupe-style eyebrows above the wheelwells are separate pieces rather than integrated into the body. The fuel filler is in the right rear fender, the opposite of all production 300SL Roadsters. In another peculiar reversal, the wipers park on the “wrong” side of the windshield.

The transmission is completely different, tucked far forward under the dash and coupled by a lengthy shift lever, the mechanism taken from a 300 sedan.

When the car was photographed in 1956, it was fitted with what became production-style bumpers and chromed side trim. Back to a race car for 1957, the bumpers and trim were removed and never replaced. Openings for front and rear bumper mounts were covered by riveted plates. The exhaust was also altered, ducted through two short, ummuffled pipes exiting from the right front rocker panel, just aft of the air vents.

This 1955 300SL/SLS prototype is a great find. The past rarely reveals itself, and seldom do we have the opportunity to see the source of the automotive icons we cherish today. Perhaps somewhere the tvvo O’Shea SLS race cars lie under faded canvas tarps. Perhaps they will be discovered, as 00009/52 was, and make that leap from ancient junk to treasured artifact.

The invaluable assistance of Scott Grundfor, Scott Restorations, Stanislav Peshcel (MBAG), Michael Riedner, David Douglas Duncan, and W. Robert Nitske in the preparation of this article is greatly appreciated.