Text by Mick Walsh, photography by Tim Scott

Classic and Sports Car Magazine, April, 2010

Named after a Hollywood icon, Ghia’s 1955 Streamline X Gilda now has the turbine power to match its sensational looks. Mick Walsh discovers how it was brought to life.

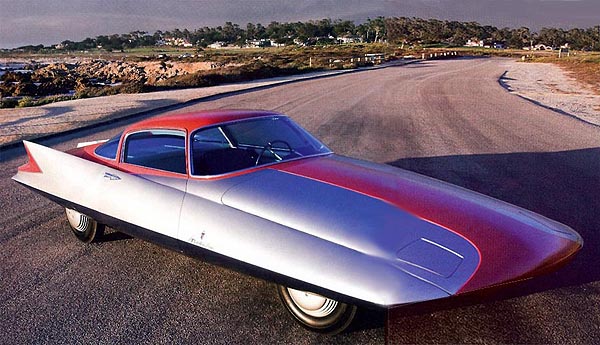

Finned wonders were the height of fashion in America during the 1950’s, but one of the most spectacular had Latin origins and was created for serious wind-tunnel research. With Chrysler’s potent V8 Hemi engines pushing the top speeds of its 300 letter cars to well over 100mph, aerodynamics had become a serious concern. The company’s new ‘Forward Look’ had proven unstable in crosswinds at high speeds, so design chief Virgil Exner commissioned Ghia’s technical director Giovanni Savonuzzi to develop airflow models and a prototype for research in the wind tunnel at Politecnico di’Torino. Born in 1911, Savonuzzi had worked in Fiat’s aviation division before joining Cisitalia after WW2 where he developed a series of aerodynamic coupes with signature high rear fins.

Compared to the flashy styling trends across the Atlantic, Savonuzzi’s research for Exner led to a purer wedge with rounded front and sides that curved under the body, while the fins ran the length of the sleek, smooth profile. Impressive wind-tunnel results recorded a startling drag coefficient of 0.2 and encouraged by the research, Exner instructed Ghia to build a full-sized car. The project’s official title was Ghia Streamline X, but Savonuzzi was infatuated with stunning Hollywood redhead Rita Hayworth and tagged the prototype ‘Gilda’ after her 1946 movie. The glamorous siren’s sexy performance in this film-noir classic earned her the nickname La Vedette Atomique, which matched the Ghia prototype.

Exner had discovered that Ghia’s workmanship was both better and cheaper than specialists at home, and the finished Gilda proved his theory. Built around a tubular chassis, the show car featured independent front suspension and a solid rear axle. The cabin had a separate platform, while its underbelly completed the full-body wrap for smoother airflow. During its recent renovation, owner Scott Grundfor found an Italian poem scratched into the black paint of the inner body. Not seen since the Gilda’s construction in 1955, the lovelorn prose referred to an intoxicating meeting and the bitter taste of separation. Could this have been Savonuzzi’s paean to the Brooklyn-born movie goddess?

Inside the low, two-seater cockpit, the trim and instruments were as stark as the outlandish body, with two large dials saddled either side of the steering column and under a painted wrap-around dashboard top. Look closely at early photographs and you can see harnesses draped over the two-tone cloth armchair-style seats.

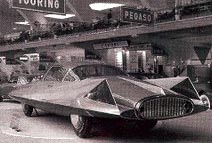

The Gilda made its debut at the Salone dell’automobile where it totally upstaged other new dream cars inside the imposing Pier Luigi Nervi-designed Palazzo della Esposizioni, including the Nardis Blue Ray and Alfa BAT 9. After the Turin show, the Gilda was invited to a special exhibition in America entitled Sports Car on Review, staged at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn. This was a huge honour for Ghia to be invited to the Ford centre in Detroit and teh non-runner was again the talk of the show, which featured such exotics as the Mercedes-Benz super-transporter, complete with 300SLR on the back. A year later Savonuzzi followed the Gilda to the US, where he headed Chrysler’s turbine division., graduating to director of automotive research before returning to Fiat in 1968.

The Gilda remained in Dearborn after the exhibition, but – partly due to its Chrysler associations – the prototype was soon hidden away. it was eventually acquired in 1969 by inveterate car hoarder Bill Harrah for his huge Reno collection. When the casino magnate died, the Gilda was bought by the Blackhawk Museum where it joined a breathtaking group of Ghia prototypes including the Chrysler Dart, also known as the ‘Super Gilda’, which was powered by a K300 V8 and featured a retractable top. When the Blackhawk collection was trimmed down before being donated to the University of California, the Gilda was offered for sale.

Respected Californian restorer Grundfor has been fascinated by concept cars ever since his grandfather took him to the Pan-Pacific Auditorium to see the latest Motorama shows. “As a kid, I was fixated with the glamour of the future,” he recalls. “Rockets and space travel were the focus of popular culture. Grandad was a superb engineer and worked for North American (Aviation). He even took me to see the X15 record-breaker. But those Motorama shows left a lasting imprint on me. Cars were presented on turntables, with a full orchestra and beautiful women.” Grundfor bought four of Ford’s prototypes when they were auctioned in 2002 and his interest rapidly filtered through the trade. Word soon reached him when the Gilda came up for sale: “I always thought it was one of the most amazing shapes and ended up buying it unseen. I had this nightmare that it might end up as a coffee-table base in a conference room, so I had to save it.”

The show car more than lived up to expectations when it arrived at Grundfor’s workshop on his ranch near San Luis Obispo: “Photos can be deceptive but I didn’t expect the Gilda to be so well-built, right down to the door-catches and seals. Despite reports that it had once been fitted with a tuned Osca 1500cc twin-cam ‘four’, it was soon clear that the Gilda had never been a runner. The aluminum brake drums were unlined, the steering was disabled and the suspension had no clearance.” Grundfor initially had no intention of making it work, but the idea slowly started to absorb him: “Something that doesn’t function is often ignored and the Gilda seemed like an unfinished project to me. When Savonuzzi moved to America to work for Chrysler in 1957, he headed its turbine programme. Because the Gilda was the first project developed in the Turin wind-tunnel, it seemed to make sense to fit a turbine engine.” Not wanting to be branded as a man who destroyed the Gilda, he was adamant that the conversion would require minimal modifications: “As historian Michael Lamm put it, ‘you’ve inherited the Mona Lisa, so don’t bugger it up’. Everything had to be reversible, because in a century’s time the running of the Gilda won’t be important.”

With little space to fit the power unit, size was a major concern and, with the help of Indiana-based specialist Bruce Linsmeyer (who owns the Howmet racer), Grundfor went for a lightweight, single-stage AiResearch unit. “These are used for auxiliary power in large aircraft and various cars have been converted including a Honda CRX.” he says. Much of the expert fabrication was done by Brad Wilcox and, with the engine running at 55,000rpm, the power transfer case to the Hydrostatic automatic gearbox was critical: “Balance and alignment were a challenge and initially it kept chewing bearings. The driveline also takes care of the braking and, if engine failure does occur, the rear end locks up. You only need the drums to hold it before moving off. “Starting up for the first time was scary. The bulkhead is pretty thin and you’re extremely conscious of the high revs behind. It’s very noisy and ear protectors are essential. It takes a long time to spool up, but the sound and feeling are tremendous – not to mention the flame-out.”

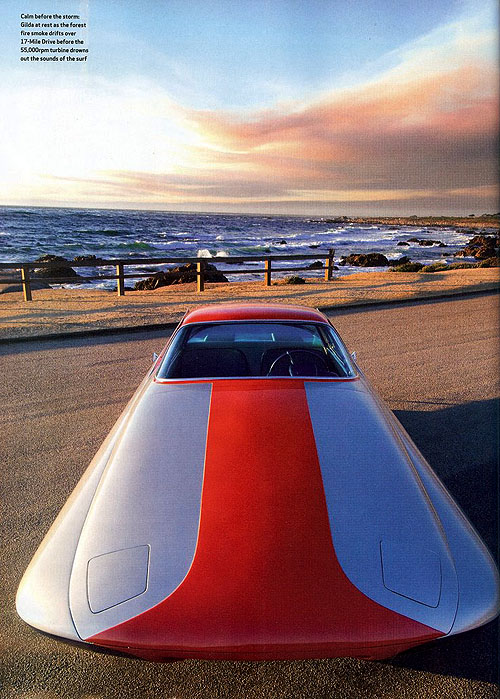

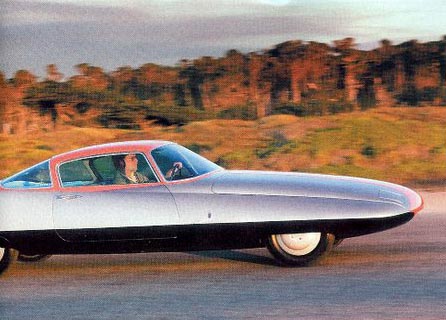

After two years of running the Gilda at events, Grundfor is now more relaxed about the procedure. He thinks nothing of firing it up inside the box trailer for our photo-shoot on Monterey’s 17-Mile drive. With the key turned on, the igniter plugs immediately begin clicking and the turbine starts the first stage as it spools up to 20,000 rpm. “It’s a 24V system and very dangerous,” warns Grundfor. “You don’t want to touch the shielding because a shock could kill you.” After 10 seconds, the engine erupts – with the resultant flame-out – before revs build to 55,000 and you’re ready to move off: “The complete start-up takes around 20 secs – I thought the revs were never going to stop climbing the first time I ran it up.”

Once the turbine is ready, you engage the Hydrostatic transmission via a T-headed lever on the floor: “The vacuum sensors are very responsive and it will lock up the rear wheels if you pull the lever back too abruptly.”

I couldn’t resist having a ride with Grundfor down the famous Pacific-coast road. Not surprisingly, the car instantly distracts visitors from the sunset. Getting in is a challenge with such a low roofline. One of the minor design modifications was to make the armrests removable but, other than two extra temperature and pressure gauges by the drive lever, the car’s interior is just as it was first displayed. Grundfor is insistent that passengers were car defenders and I soon discovered why. As we pull away, the noise of the turbine is deafening. Conversation is impossible so you resort to sign language. It’s a weird sensation, cruising at just 30mph with such a din. The Gilda immediately draws a convoy of admirers behind and Grundfor is relieved to stop. With the ash fallout from last summer’s forest fires, the sky turns a brooding tone at sunset and the Gilda looks even more surreal as its two-tone paint turns luminescent. This flamboyant, finned wonder could have landed straight out of The Jetsons.

Such a spectacular car is guaranteed invites to the most prestigious events, but the highlight for Grundfor was a trip back to Turin where the Gilda made its debut in ’55. “The city had been nominated as the first World Design Capital,” he remembers,” and teh celebrations included a dream car display in the restored Agnelli Pavilion where the auto shows were held in the ’50s. Modulo, Carabo, Zero, Marzal – all the greatest concepts were promised but I heard nothing after the initial invite. I was about to pull the plug when Luciano Bosio – the former director of ItalDesign – called and insisted that my car had to be there because it was the central exhibit.”

To see the Gilda displayed in the very hall where it made its debut was special, but best of all was a chance meeting with Savonuzzi’s daughter Alberta at the exhibition: “It was fascinating to hear her memories of her father. He was born in Ferrara and was a typical Italian gentleman engineer. She said he was a remote character and always wore a suit, even when working on clay bucks in the studio. Alberta also recalled the plasticine wind-tunnel models for the Gilda.”

Grundfor couldn’t resist asking about the inspiration for the nickname: “Alberta said that Rita Hayworth was her father’s favourite actress – in his eyes, she was the most beautiful woman in the world. In the late 1940’s, Giovanni was involved with a special Cadillac built for Prince Aly Khan, who was then married to Hayworth. Alberta said her father was quite a ladies’ man and maybe something happened between them. When he started on the Ghia, he was determined to create a car worthy of her name.”

As if the Turin design exhibition wasn’t thrilling enough, Grundfor arranged for the Gilda to be displayed at ItalDesign until the following April so that it could appear at the swish Villa d’Este concours. It was accepted as a static exhibit, because the organisers believed it was still a non-runner, but the Italians were stunned when Grundfor announced that he was going to start the jet engine and drive it past the judges at the famous Lake Como hotel. Jaws dropped and the show car scooped the people’s choice award.

Future events for the Gilda include the Amelia Island Concours from 12-14 March, where it will feature in a special display of Motor Trend cover cars. “At one point,” says Grundfor, “I had the crazy idea of taking it to Bonneville just to see what it could do. I’d never forgive myself if something happened, but I’d love to show it at the Goodwood Festival of Speed.” With this year’s Viva Italia theme, 2010 would be perfect for the Gilda’s British debut. Just imagine it displayed alongside one of the Cistalia ‘Razzo’ sports cars, or with a Hayworth lookalike as a tribute to the unsung Savonuzzi.