This car is the starting point of a multi-generation automotive legend, to which 500,000 cars can trace their genes. It is the 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SLS and, like most of its ‘children’ — every sporting Merc that has followed — chassis 8427198118/1 is a stupendous drive.

This car is the starting point of a multi-generation automotive legend, to which 500,000 cars can trace their genes. It is the 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SLS and, like most of its ‘children’ — every sporting Merc that has followed — chassis 8427198118/1 is a stupendous drive.

The car’s creators were legends in Mercedes history, outlined in Karl Ludvigsen’s Mercedes Benz Quicksilver Century, which traces the SLS legacy back to October 1954. Rudolf Uhlenhaut spearheaded the effort, working under Fritz Nallinger. The two engineers meshed like a hand in glove. Crafting the SLS’s sensational shape were chief designer Karl Wilfert and stylist Friedrich Geiger. Wilfert had a key role in defining Mercedes cars “design profile” in the early ’50s, which led to him setting up the firm’s styling department in 1955. The SLS may have been its first project.

Following the Daimler-Benz board’s October 1954 product briefing on an open-air SL, the team went to work. But they immediately encountered problems. The SLS was developed and built in the competition department alongside the W196 racers, the experience of which showing that, without a proper roof like the then recently announced Gullwing, the chassis would require stiffening.

After much experimentation in trying to reinforce the frame, they realised that they needed larger diameter tubes made of heavier gauge steel. They also altered the existing structure’s intricate design from the bulkhead back to provide proper space for the doors and luggage compartment.

While the chassis was being sorted, Geiger started sketching away, with Wilfert looking intently over his shoulder. The resulting drawings portrayed a beautiful, elegant, purposeful car – one that did not suffer from the compromises found in the Gullwing.

An internal document dated August 15, 1955 states the car would be finished by September. A memo from November 7 gives insight into Mercedes’ thorough engineering: nothing major needed to be addressed. Instead it notes mundane items such as the dimmer switch and the soft-top being difficult to operate.

When news seeped out, it couldn’t have differed more from the clamour that greets today’s new models. The SLS’s existence was first reported in the October 12, 1956 issue of Collier’s, a sophisticated, widely read American magazine far removed from the growing automotive publishing industry. The story was by David Douglas Duncan, a good friend of Pablo Picasso, who owned a 300SL Gullwing that he picked up at the factory in 1956.

During a visit, Duncan was approached about writing an article, appropriately titled The Secret SLS and, as Road & Track noted in its December 1956 issue: ‘Collier’s scooped us all on photos of the new open model, which they say will be called the 300SLS.’

Duncan wrote: ‘Though much technical data is still cloaked in secrecy, factory officials have released enough details with these exclusive Collier’s photos to give a clear idea of what that streaking shape really is when standing still…

‘Designed by racing experts for sportsmen to whom the final product is the only consideration, the 300SLS is unlikely to become the second car in every man’s garage. It is meant to be the crown jewel of all sports cars.’

It was several months before the SLS, by then called the 300SL, appeared in other publications around the globe. It was used in Mercedes-Benz publicity shots and sales material, and Friedrich Geiger’s original sketches of the SLS also appeared in the literature.

As the company prepared the first production SL Roadster in early 1957, the SLS served as another starting point in the SL saga. Paul O’Shea had won the Sports Car Club of America’s championship in 1956 300SL coupe so Uhlenhaut beckoned him to Germany to test the SLS, eyeing the SCCA’s 1957 season.

O’Shea travelled to Europe to help with the press presentation. Then he drove the SLS for all it was worth, testing it at Hockenheim, the Nürburgring and the Solitude track. Modifications during its development programme included Dunlop-type disc brakes fitted to the front wheels, a first for Mercedes.

Following that intensive winter testing, two competition cars were made. They were also called the 300SLS by Mercedes and were sent to America where they easily won 1957’s Class D championship, accumulating three times as many points as their nearest competitor, Carroll Shelby’s Maserati.

That the SLS acted as the inspiration for a competition 300SL Roadster is fascinating considering its ‘earlier’- and for two decades overlooked – history. According to Mercedes historian W Robert Nitske, the SLS was not originally built in 1954-’55, but in 1952 when Stuttgart returned to racing. In November 1980, Nitske wrote a letter to the car’s owner, Lloyd Ikerd. Referring to a note found in Mercedes’ archives, the letter states ‘the car was a vehicle which was used in testing and according to the meagre information we found in the papers there, it was the car which Fitch drove in the PanAmericana race in 1952… Apparently the car was used by the factory in different forms for extensive testing for racing events and the final version with the injected engine was then sold to a customer, eventually.’

Nitske’s research revealed that the SLS was originally 300SL chassis 00009/52. Part of the firm’s anticipated ’52 competition programme, it was homologated in Germany on May 26 with number 101977 and license W 83-3786. It was then a gullwing-doored coupé.

The car first raced on June 14 at the Le Mans 24 Hours where it finished second overall. Its next outing was at the Nürburgring sports car race on August 3. Because this was a sprint, Mercedes lightened 00009/52 and three other SLs’ coachwork by changing them to roadster bodies: 00009/52 finished third. Several weeks later it competed on the Carrera PanAmericana. As Nitske’s letter observes, piloting it was American John Fitch, a former SCCA champion (C&SC, Feb ’03). In contention for a top five finish, Fitch was disqualified on the last leg.

Its competition career ended then but, unlike its racing brethren, this Mercedes went on to have a second life as the SLS. It remained the property of Daimler-Benz AG until July 13, 1965 when Karl Jurgen Britsche of Hamburg bought it. Paperwork states the SLS received its 8427198118/1 chassis number one day earlier. The same documents also state that no number was stamped into the chassis because the car was used as a prototype or test car.

In April ’68, Britsche sold it to Arthur von Windheim, who owned the SLS until 1979 when American Lloyd Ikerd bought it. Ikerd then contacted Nitske, revealing the car’s past life in the process. American 300SL expert Scott Grundfor purchased the car in 1987: all he knew was that “it was something special” but most appealing was its rust-free original condition. His crew then began disassembling it. “I knew of its PanAmericana connection,” he recalls, “thanks to the letter from Nitske. The Gullwing Group’s Roadster Register also listed it as the Number 6 car that ran at the race.”

Unusual parts uncovered during the strip down backed this up, such as the magnesium intake manifold and sump. They also found the disc brakes from the 1956-’57 test sessions.

As they toiled away, the SLS caught the eye of Naohiro Ishikawa, so much so that the Japanese collector bought the car. It then made its debut at the Monterey Historics/Pebble Beach weekend in 1991. Six years later the unique Merc returned to Pebble, then owned by Bob Meyer of southern California. The car was still in immaculate condition, so Grundfor gave it a good detailing. The SLS won its class.

During this appearance, an episode occurred that shows Duncan’s Secret SLS title was still applicable. A senior Mercedes executive walked around the fabulous roadster, with a quizzical look on his face. He finally paused, then shook his head and muttered: “We never built that car!” Rather than being viewed as a comment on its authenticity, this observation is amusing because a few years earlier the factory museum had published a catalogue featuring the SLS, stating that it was the 300SL prototype. Seven pages were devoted to it, lavishly illustrated with Duncan’s breathtaking photography.

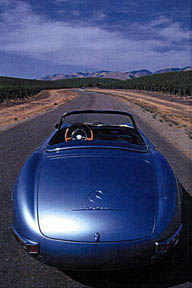

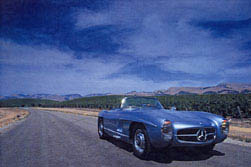

Today it looks as if it might have driven straight out of those photos. It may appear similar to the production 300SL Roadsters, but every body panel is different, more voluptuous, sensual and taut.

The result is a hand-built machine so beautiful, so sensational, it equalled anything the Italians were making at the time. Its lustrous paint shows off every line perfectly, and the chrome accents set everything off like intricate pieces of jewelry. The interior is decorative and restrained. Its unique wood steering wheel is the perfect complement to the sea of leather. Like the exterior, the chrome accents are ideal highlights. The firm seats are comfortable, with good bolstering for your lower back and on the sides. Legroom is slightly limited, and a long gearlever juts out from under the dash, a remnant from its competition days.

The car’s 3-litre straight six is a torquey, civilised unit that can get your juices flowing when run hard. The clutch is relatively light and progressive so that it doesn’t need much slipping. Pedal travel is a little long, but nothing out of character for that era’s performance cars.

The 250bhp motor is extremely tractable, able to pull from 1200rpm. It doesn’t hiccough or hesitate when you floor the accelerator, but simply pulls harder with each 1000rpm increase. Cross 3500 and the acceleration is crisp, giving you a nice shove in the seat.

The power plant is a little lumpy low down, likely due to the cam profile but, when you are hard on it, has a nice guttural sound that becomes more fluid the higher the revs rise. Then the twin exhausts, which are anything but subtle, dominate the engine’s silky song.

Once moving, the steering lightens but feedback is wooden at best. It loads up properly when you blast through a curve, turn-in becoming more firm. A little slop prevents it from having great accuracy, though that doesn’t stop you from enjoying pushing the SLS through turns. The suspension dishes out a lovely ride, relatively communicative but not jarring. There is a fair amount of understeer and body roll through tight corners, yet everything is quite controllable. Fast sweepers are just as much fun. The SLS’ suspension soaks it all up, and the chassis is commendably rigid – and better than Ferrari’s contemporary 250MM.

This unique machine is not just stunning and a joy to drive. The 300SLS set the standard for the four generations and 500,000-plus SLs that followed – a legacy that continues to unfurl.

This article originally appeared in the September 2003 issue of Classic & Sports Car magazine.